“What a strange thing! To be alive beneath cherry blossoms.” – Kobayashi Issa

We do not know what the world will look like after COVID-19, but we know it will be different. In our former lives, we bemoaned how overscheduled our children’s and our lives were. No doubt, we are still very busy juggling work and domestic obligations, but there is more space for feelings and reflection. And sometimes, those feelings—and the accompanying emotions we use to express those feelings—can be quite challenging to tease out, for ourselves and our children.

For instance, a colleague raising her son as a single parent recently shared how clingy her son had become in the last couple of weeks. Normally self-sufficient, he would not leave her alone, making it difficult for her to carve out time for her work. His behavior was confusing her, as they had been together more over the last month, not less. My friend’s first reaction had nothing to do with feelings; like many of us, she ticked off hunger, illness, and fatigue before realizing the typical ways we use to explain mysterious behaviors might require more detective work and empathy.

Parents are also not immune to unusual expressions of emotion. As Chloe Cooney points out in her article, “The Parents Are Not All Right” (which I shared for last week’s Living Room chat), even in the best of circumstances, we are struggling. We may feel guilty for not doing enough for work or family and confused over our inability to soothe our children’s ups and downs, or accurately define what’s making them act a certain way.

We are all longing for calm in chaos, and we’re scrambling to adjust to the absence of our regular routines, which create rhythm and purpose in our lives. It is important to remember that as individuals, we cannot solve problems that were systemically created. And sometimes, in our efforts to control chaos, we inadvertently create more chaos, particularly for ourselves. So, if we find ourselves acting more short-tempered, or scattered, or prone to shedding tears, maybe it is because we are feeling a loss of control, insecurity, or worry about the unknown ahead.

Last week, I listened to Cheryl Strayed’s conversation with the prolific travel writer, Pico Iyer, who currently lives in Japan among the briefly-blooming cherry blossoms. Iyer observed that we love the cherry blossoms because they don’t last; they represent how everything is constantly changing in our fragile, mortal world. Japanese culture emphasizes life as “joyful participation in a world of sorrow.”

Like the words “joy” and “sorrow” in the quote above, many juxtaposed feelings are at play in our lives right now—or, more probably, sheltering in place offers us more time and space to notice and process our emotional experiences. This can be challenging if we are not used to deciphering and making sense of our feelings, especially in this intense time.

I encourage you to get curious about your and your loved ones’ feelings. For example, how often in your “pre-pandemic” rushed morning routine did you ask your children or partner, “How are you doing?” and really listen? How did you respond if the answer is, “Well, I’m feeling anxious and stressed, and I didn’t sleep well.” If you are like me, the likely response was something like, “Well, we can talk about it in the car on the way to school.” Understandable, but not ideal.

When we cannot stop where we are and address feelings in the moment, they tend to come out sideways as emotions or actions far removed from the original feeling. They can show up as a grumpy spouse who snaps at a simple request, a call from a teacher when your child has an outburst in class, your own lack of patience with co-workers or friends. By the time the feeling has become an expressed emotion, you may not be able to find your way back to the source.

These days, we have the luxury of really listening when we greet our children or our partner in the morning and ask how they are doing. And when we genuinely attend to how they are feeling, suddenly the expression of emotion becomes far less complicated or mysterious.

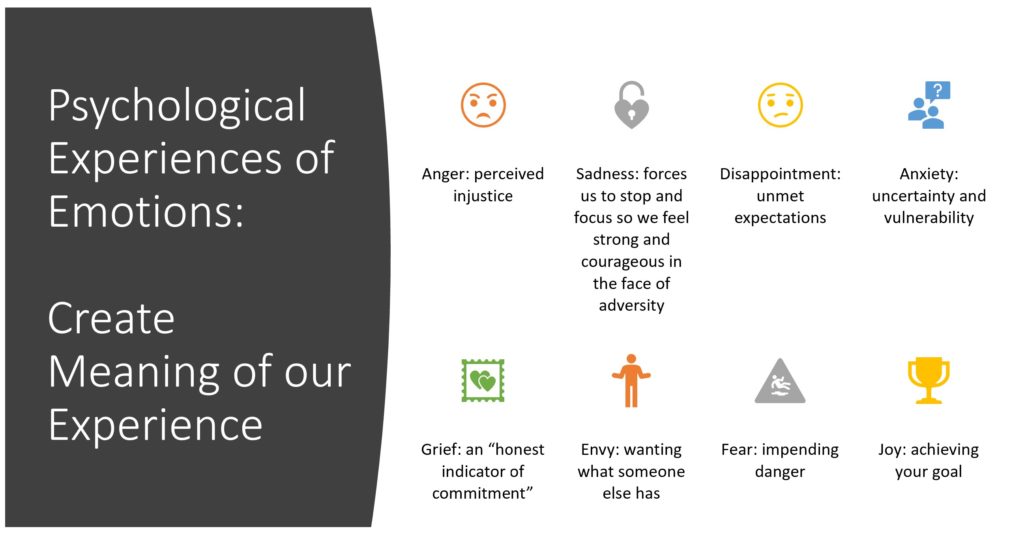

Dr. Marc Brackett urges us to give ourselves “permission” to express emotions. In his book Permission to Feel: Unlocking the Power of Emotions to Help Our Kids, Ourselves, and Our Society Thrive, Dr. Brackett urges us to approach our feelings or those of family members with curiosity rather than frustration. This “curiosity” mindset helps us better understand what’s at the heart of a child’s (or our own) behavior. Understanding what emotions are telling us is equally important:

- Anger often stems from a perceived injustice

- Disappointment is usually about unmet expectations

- Anxiety is about uncertainty and vulnerability

- Fear is anxiety about impending danger

- Envy is the perception that someone else is better than you in some way

- Jealousy is wanting what someone else has

- Joy is the expression of relief and pride at achieving a goal

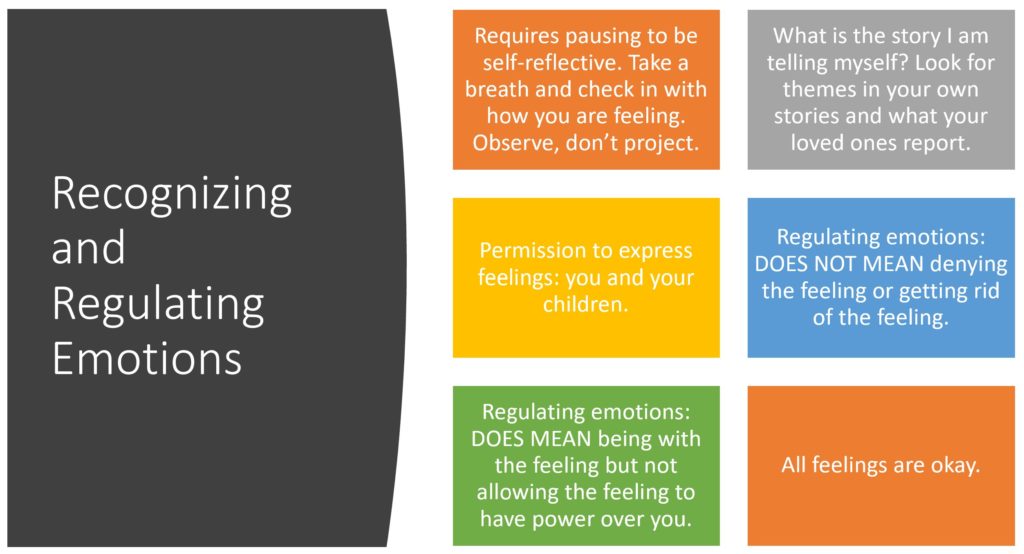

Dr. Brackett outlines strategies for us to recognize and regulate our emotions. They include:

- Pause to be self-reflective. Take a breath and check-in with how you are feeling. Observe, don’t judge.

- Ask yourself what you are expressing and if it matches what you are feeling (or your child or partner is showing/feeling). For instance, if your child is yelling and crying, telling you she misses sleepovers at Grandma’s home, she is expressing disappointment, not anger. You can adjust your response accordingly.

- Regulating emotions does not mean denying or getting rid of the feeling; instead, stay with the feeling but don’t allow it to have power over you.

- All feelings are okay. Sometimes our meta-emotions (feelings about feelings) prevent us from facing our feelings. Shame and embarrassment, in particular, can lead to behaviors that do not reflect the underlying feeling. How many of us have felt ashamed about a perceived inability to cope, and have expressed those feelings through tears or frustration? You’re not alone.

- We judge how we should feel based on expectations (sometimes a result of gendered or cultural expectations, for instance). Sometimes it is because we erroneously think everyone else is handling things beautifully (see: envy) or because we are judging our feelings on how things used to be (see: disappointment).

Helping ourselves and our children make meaning from their emotional experiences is key to becoming fully self-actualized humans, able to realize our talents and potential.

As parents, modeling calm, approaching emotions with curiosity, and giving yourself and your children permission to feel will go a long way toward reducing anxiety. These life-long, invaluable skills lay the groundwork for the courage, flexibility, and compassion we will require to re-envision our world as a better, more equitable, more beautiful place.

How we will reconstruct our society remains to be seen, but I hope we do so intentionally and purposefully. We would benefit from listening to our values and to attending to our and our families’ inner lives to prioritize what truly matters.

Warmly,

Laura

Laura Konigsberg

Head of School

lkonigsberg@turningpointschool.org